Footage shot dead-on after which organized in rows or grids comprise virtually each contribution to “Typologien,” a survey of Twentieth-century German images on the Fondazione Prada in Milan. No horizon line is even mildly crooked, and all fall the place they must—within the image’s backside third—or else are eradicated by means of a backdrop or an aerial view.

That’s not stunning; Germans are well-known for his or her love of guidelines, loads of which, relating to images, they invented themselves. However the present, curated by Suzanne Pfeffer of Frankfurt’s Museum für Moderne Kunst (MMK), emphasizes the beliefs underpinning these guidelines and the motivation behind the formal decision-making. It’s a refreshing return to type at a second when images criticism and exhibitions are putting outsized emphasis on content material, a wholesome reminder that ethics and aesthetics have lengthy been seen as one and the identical.

The present begins with plant photos by Karl Blossfeldt, Lotte Jacobi and Hilla Becher; these proceed the work of German Naturalists who, within the 18th century, noticed artwork and science as one. Proper off the bat we see one of many issues inherent in typologizing: Becher’s black backgrounds, incongruous with the uneven mild on her flowers and leaves, are so darkish and flat that it’s apparent they had been manipulated within the darkroom. Her try at “objectivity” privileges good photos over naturalistic ones, preferrred specimens over ones randomly chosen. Efforts to take away the human hand from photos can usually imply extra manipulation, not much less.

Amid so many good plant photos, Thomas Struth’s photograph of a sunflower simply starting to unfurl stands out with its awkwardly clenched petals. Its extra conventionally stunning stem-mate is blurry and lower off by a nook. Titled Small Closed Sunflower-No° 18 (1992), the photograph invitations extra wanting than the opposite flowers in Struth’s row, which, with their dew drops and use of a macro lens, really feel so much like screensavers: boring of their magnificence.

Andreas Gursky provides this part’s grand floral finale with Untitled XVIII (2015), an aerial view of flowers planted in astonishingly neat rows. The print is so massive that the topic is defamiliarized, wanting extra like a portray than {a photograph}. Gursky’s images doesn’t render a topic extra comprehensible however, reasonably, extra enigmatic.

Gursky and Struth, like a number of artists within the present, studied with Bernd Becher on the Düsseldorf Artwork Academy. (Hilla, his spouse, was not formally employed there, however tellingly, many artists describe themselves as college students of “the Bechers.”) The present borrows its title, “Typologien,” from the couple’s main collection, proven within the exhibition’s heart. It includes grids of photographs of water towers and buildings shot from a number of angles. Every view is fastidiously calculated and evenly spaced, the constructing all the time dead-center within the body.

Unsurprisingly, the work of the Bechers’ college students betray each affect and insurrection. Sybille Bergmann cleverly used her academics’ strategy on a constructing’s inside, photographing each lounge in a single condo complicated. Every room has the identical format, every image the identical lighting from the identical window; what stands out amid the monotony are the private touches that make a home a house. On view reverse the Bechers’ “Typologien” collection, Bergmann’s pictures exude heat humanity—no small feat for a grey grid.

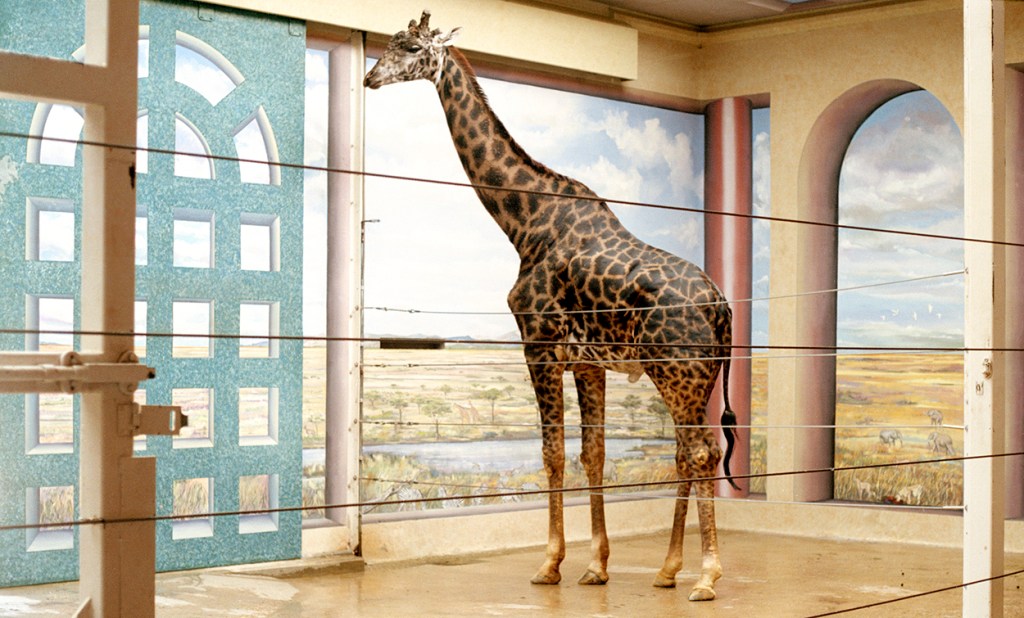

On the identical wall, Candida Höfer takes on specimens like her forebearers, however emphasizes their context as a substitute of burning it black. Her pictures of lone animals in zoos emphasize the solitude and squalor any organism may endure when displaced from its habitat for human research. Höfer features a giraffe—its neck looming amongst painted clouds—and a mournful Moo Deng doppelganger: a child hippo all shiny and unhappy. The artist had by no means particularly excited me earlier than, however contextualized right here, it was evident that her retort to all of the typologizing was important.

Important as a result of in Germany, of all locations, typologizing had horrendous penalties. On view in a smaller gallery upstairs is a significant collection of portraits by August Sander, who got down to {photograph} each “kind” of individual within the Weimar Republic within the Twentieth century, starting in 1911. His venture is the present’s largest in quantity and influence—the Bechers drew a lot affect from him—although he by no means completed the 600 portraits he got down to take, and misplaced loads to fires and Nazis. Sander was serious about physiognomy—what the construction of a face may reveal about an individual’s character—which could appear a foreboding progenitor of Nazi eugenics. However the Nazis banned Sander’s venture, arresting his son Erich, who died in jail, and drafting his different son Gunther, who fought for the incorrect facet of historical past. For a lot of artists, the World Wars would destroy any religion in rationality, however Sander clung to his perception in images’s neutrality and the significance of paperwork, persevering with to {photograph} wealthy and poor, oppressor and oppressed.

Amid his many portraits—every exuding pathos and individuality, all onerous to typologize with out assistance from captions—I discovered myself tiptoeing round each nook, questioning if I’d see a Nazi, and if I’d acknowledge him once I did. First I questioned this of the artwork after which of life, previous after which current.

From Sander, the present manages to softly ease us to lighter, even humorous work, first with photos from the Eighties by Christian Borchert, exhibiting East German households stuffed with character posing of their residing rooms. Adjoining to these are Struth’s large coloration photos of fancy households that really feel significantly extra lifeless and staged, amongst them Gerhard Richter’s quartet. Subsequent is a row of ears that Isa Genzken photographed, then blew up; large and headless, they appear positively unusual. After which a giant chuckle earlier than issues get darkish once more: Rosemarie Trockel, the funniest German, tries the Bechers’ many-angle transfer on a couple of canines who, sitting and even smiling for her digital camera, will need to have been excellent boys.

The final room is dedicated to work by Richter, ominously enclosed. Inside is a part of his famed “Atlas” collection (begun within the Nineteen Sixties), with a range centered on harrowing scenes from the Holocaust. Richter grouped and organized these photographs on massive sheets, emphasizing the sheer amount of them; there may be extra awfulness on view than one can take.

I occurred to enter the room as two kids, talking Italian, had been seeing these photographs seemingly for the primary time. That they had many questions. Linguistically, I may solely form of observe, however on one other stage, I understood.

It made me wish to say this: images, as an artwork type, appears caught proper now, left adrift within the wake of ample criticism that the digital camera is inherently violent and extractive, burdened by uneven energy dynamics—all of which is true. Footage of mass graves and loss of life camps in “Typologien” are not any exception; taking a look at them feels form of incorrect, very uncomfortable. However I’m glad these children noticed them, regardless of the knot in my abdomen whereas watching them see, a knot that has returned as I write. I believe now of images of Gaza and the best way they present us what colonialism has most likely all the time appeared like, solely a lot of it happened earlier than images was invented. Would photos have helped then? It’s onerous to know, but it surely does appear sure that metaphoric violence has nothing on the actual factor.